Structural Imbalances and Yoga Practice

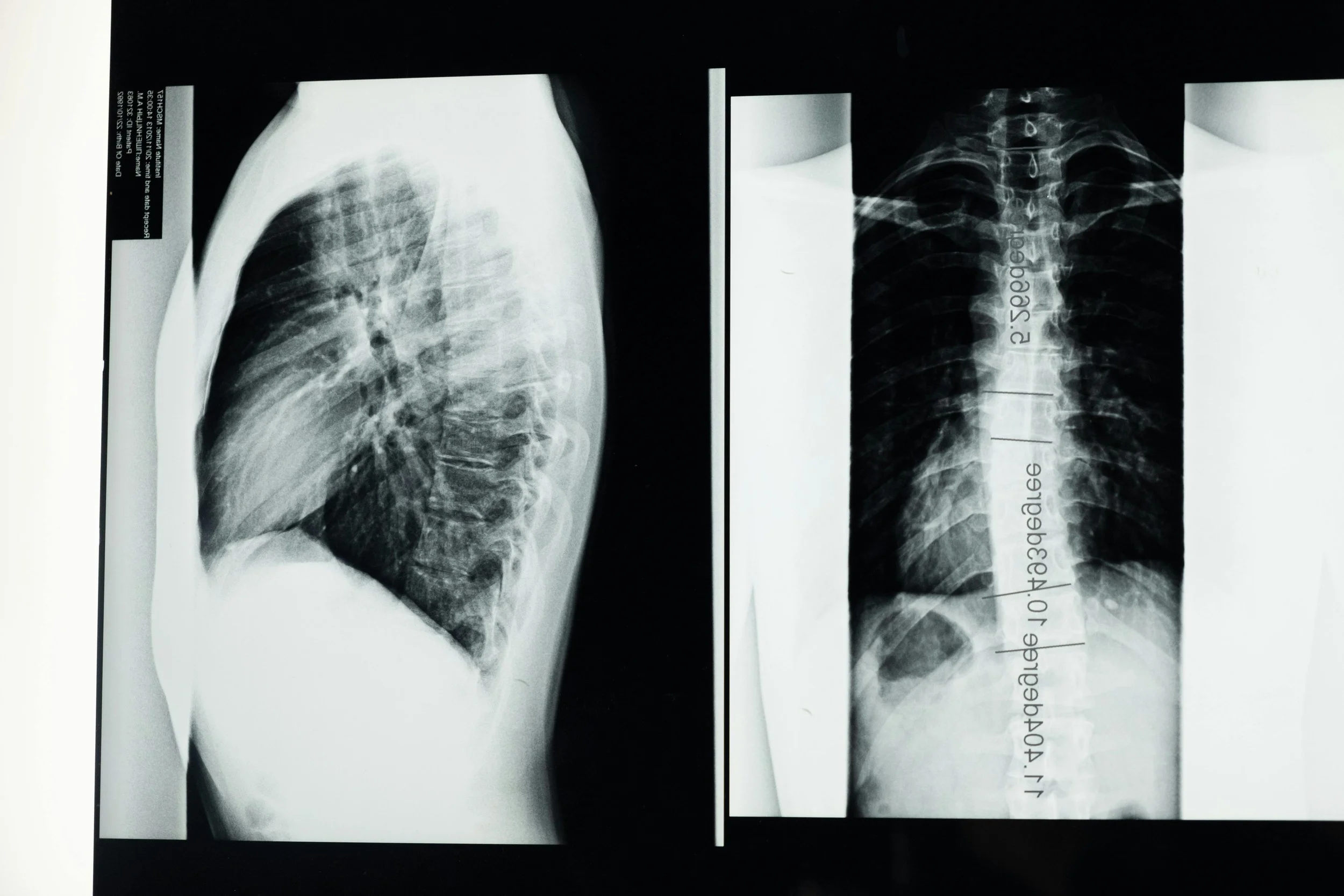

Structural imbalances are a reality for most adults, not an exception. Very few bodies are symmetrical, evenly loaded, or perfectly aligned. Differences in shoulder height, pelvic rotation, spinal curves, or weight distribution between the feet are common and often develop gradually through daily habits, work demands, injuries, or long-standing movement patterns.

Photo by Cottonbro Studio

In many cases, these imbalances do not cause immediate pain. The body adapts well, until it is asked to move more, move differently, or sustain effort over time. This is often when people notice discomfort during exercise, including yoga, even though yoga is generally perceived as a corrective practice.

Understanding how structural imbalances are addressed overall, and where yoga fits within that picture, is essential for practicing safely and effectively.

Understanding Structural Imbalances and Common Interventions

Structural imbalances can be broadly divided into two categories. Some are structural in nature, involving bone alignment, leg length discrepancies, or spinal curvature that cannot be changed through exercise alone. Others are functional, meaning they arise from muscular tension, weakness, or habitual posture and are potentially modifiable with movement and therapeutic intervention.

Because of this, structural imbalances are rarely addressed through a single solution. Instead, they are managed through a combination of approaches, depending on severity, symptoms, and individual goals.

Postural retraining is often the first line of intervention. Many imbalances are reinforced by prolonged sitting, asymmetrical workstations, or repetitive daily movements. Improving awareness of posture and movement habits can reduce ongoing strain, but habit change alone is rarely sufficient once compensation patterns are established.

Strength training and physical therapy are commonly used to address muscular imbalances. These approaches focus on restoring strength, coordination, and joint control, particularly when one side of the body is consistently underperforming. They are especially useful when imbalance is driven by weakness rather than restriction.

Chiropractic care is another option that some individuals choose as part of a broader strategy. Chiropractic assessment focuses on joint alignment and mobility, particularly in the spine and pelvis.

Manual adjustments or mobilization techniques may help improve joint motion in areas that are restricted, which can make movement practices feel more accessible. A chiropractic treatment does not replace active movement or strengthening, but it can be a supportive tool when joint restriction limits progress.

Medical evaluation may be necessary when imbalances are associated with persistent pain, neurological symptoms, or functional limitations. In those cases, identifying underlying conditions is critical before engaging in corrective exercise.

Within this broader landscape, yoga serves a distinct role. It is not a diagnostic tool, nor is it designed to structurally realign bones. Its value lies in how it influences movement quality, awareness, and muscular balance over time.

Yoga’s Role in Working With Structural Imbalances

Yoga is often misunderstood as a practice that creates symmetry. In reality, its greatest benefit for structurally imbalanced bodies is learning how to move well within existing asymmetry. Yoga teaches practitioners how to distribute effort, recognize compensation, and develop control rather than force.

When practiced thoughtfully, yoga can reduce the impact of imbalances by improving how the body manages load and transitions through movement.

Awareness as the Foundation of Change

One of yoga’s most powerful effects is increased evolationyoga.com. Slow transitions, sustained poses, and breath awareness make differences between sides more noticeable. A practitioner may observe that one hip drops in standing poses, one shoulder bears more weight, or one side fatigues faster.

This awareness is not meant to correct the body into symmetry, but to inform decision-making. Recognizing asymmetry allows practitioners to modify depth, duration, and effort appropriately rather than pushing both sides equally regardless of sensation.

Over time, this awareness often leads to improved coordination and reduced strain.

Working With Asymmetry Instead of Forcing Symmetry

In structurally imbalanced bodies, forcing symmetrical shapes can increase stress. Yoga becomes safer and more effective when poses are adapted to the individual rather than the idealized form.

This may mean allowing one knee to bend more deeply, adjusting foot placement in standing poses, or using props to support uneven weight distribution. These choices reduce compensatory tension and allow muscles to engage more evenly.

Yoga’s flexibility as a practice makes it well suited to this approach when teachers and practitioners prioritize function over appearance.

Strengthening Without Overloading

Structural imbalances often coexist with uneven strength. Yoga supports strength development through controlled, bodyweight-based engagement that can be adjusted easily.

Poses such as modified lunges, supported standing balances, and low-load arm-bearing postures allow practitioners to build strength without overwhelming joints. Emphasizing slow engagement and controlled exits from poses further supports stability.

This approach is particularly useful for individuals transitioning from injury or managing long-standing asymmetry.

Improving Mobility Where It Is Safe and Appropriate

Yoga encourages joint mobility, but in the context of structural imbalance, not all joints require increased range of motion. Some areas are already hypermobile and rely on surrounding stiffness for stability.

A well-structured yoga practice improves mobility in restricted areas while maintaining control in areas that already move easily. This balance reduces the risk of overstretching and supports joint integrity.

Gentle, breath-guided movement is more effective for this purpose than aggressive stretching.

The Role of Breath and Nervous System Regulation

Structural imbalance is not purely mechanical. Chronic tension, stress, and protective movement patterns all influence how the body holds itself.

Yoga’s emphasis on breath helps regulate muscle tone and reduces unnecessary guarding. This is particularly relevant for people who have lived with imbalance for years and developed subconscious protective habits.

By calming the nervous system, yoga allows movement to occur with less resistance and strain.

Long-Term Consistency Over Short-Term Correction

Structural imbalances rarely change quickly. Yoga supports gradual adaptation through consistent practice rather than dramatic intervention.

Practicing two to three times per week, focusing on quality of movement rather than intensity, often produces better outcomes than sporadic, high-effort sessions. Progress is measured in comfort, confidence, and functional ease rather than visual symmetry.

Integrating Yoga With Other Approaches

Yoga works best when integrated with other supportive strategies rather than used in isolation. When chiropractic care, physical therapy, or strength training are part of a person’s plan, yoga can enhance those efforts by improving awareness and movement efficiency.

Communication between practitioners and healthcare providers ensures that yoga supports rather than conflicts with other interventions.

A Functional Perspective on Balance and Yoga

Structural imbalance is not a flaw to eliminate, but a reality to manage intelligently. Yoga provides a framework for doing so with attention, control, and respect for individual structure.

When practiced with this understanding, yoga becomes a sustainable tool for improving movement quality and reducing strain, regardless of whether the body is perfectly symmetrical or not.